What is prostatitis and how is it treated?

Prostatitis, or inflammation of the prostate, is more common than you might think — it accounts for roughly two million doctor visits every year. The troubling symptoms include burning or painful urination, an urgent need to go (especially at night), painful ejaculations, and also pain in the lower back and perineum (the space between the scrotum and anus).

Prostatitis overview

There are four general categories of prostatitis:

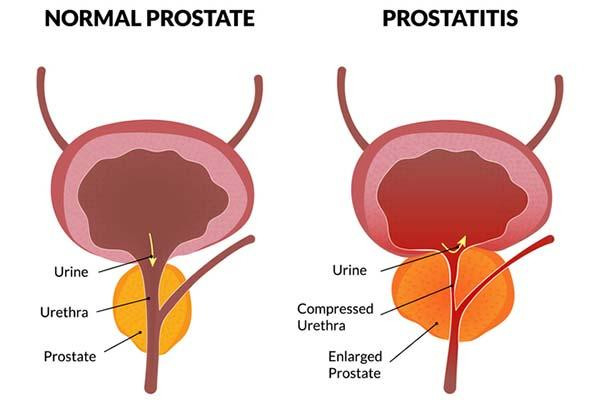

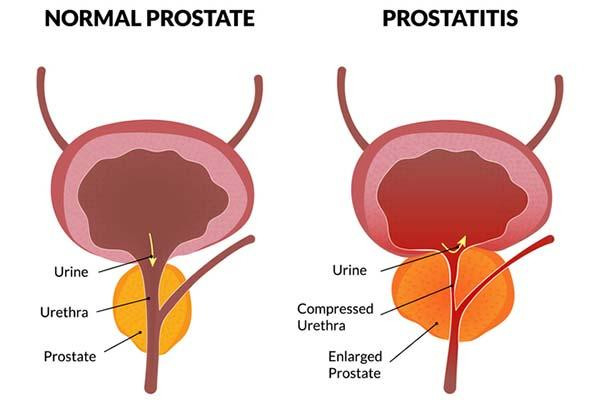

Acute bacterial prostatitis comes on suddenly and is often caused by infections with bacteria such as Escherichia coli that normally live in the colon. Men can suffer muscle aches, fever, and blood in semen or urine, as well as urogenital symptoms. Acute inflammation can cause the prostate to swell and block urinary outflow from the bladder. A complete blockage is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Depending on symptom severity, hospitalization may be necessary.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis results from milder infections that sometimes linger for months. It occurs more often in older men and the symptoms typically wax and wane in severity, sometimes becoming barely noticeable.

Chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, also called chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), is the most common type. CPPS can be triggered by stress, urinary tract infections, or physical trauma causing inflammation or nerve damage in the genitourinary area. In some men, the cause is never identified. CPPS can affect the entire pelvic floor, meaning all the muscles, nerves, and tissues that support organs involved in bowel, bladder, and sexual functioning.

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis is diagnosed when doctors detect white blood cells in prostate tissues or secretions in men being evaluated for other conditions. It generally requires no treatment.

Both acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis can cause blood levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) to spike. This can be alarming, since high PSA is also indicative of prostate cancer. But if a man has prostatitis, then that condition — and not prostate cancer — may very well be the reason for the rise in PSA.

Prostatitis treatments

Fortunately, research advances are leading to some encouraging developments for men suffering from this condition.

Antibiotics called fluoroquinolones are effective treatments for acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis. A four-to six-week course of the drugs typically does the trick. However, bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolones is a growing problem. An older drug called fosfomycin can help if other drugs stop working. PSA levels will decline with treatment, although that process may take three to six months.

CPPS is treated in other ways. Since it is not caused by a bacterial infection, CPPS will not respond to antibiotics. Medical treatments include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, alpha blockers including tamsulosin (Flomax) that loosen tight muscles in the prostate and bladder neck, and drugs called PDEF inhibitors such as tadalafil (Cialis) that improve blood flow to the prostate.

Specialized types of physical therapy can provide some relief. One method called trigger point therapy, for instance, targets tender areas in muscles that tighten up and spasm. With another method called myofascial release, physical therapists can reduce tension in the connective tissues surrounding muscles and organs. Men should avoid Kegel exercises, however, which can tighten the pelvic floor and cause worsening symptoms.

Acupuncture has shown promise in clinical trials. One study published in 2023 showed significant improvements in CPPS symptoms lasting up to six months after the acupuncture treatments were finished. Mounting evidence suggest that CPPS should be treated with holistic strategies that also consider psychological factors.

Men with CPPS often suffer from depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues that can exacerbate pain perception. Techniques such as mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for CPPS can help CPPS sufferers develop effective coping strategies.

Comment

“An accurate diagnosis is important given differences in how each of the four categories of prostatitis is treated,” said Dr. Boris Gershman, a urologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School. PSA should also be retested after treating bacterial forms of prostatitis, Dr. Gershman added, to ensure that the levels go back to normal. If the PSA stays elevated after antibiotic treatment, or if abnormal levels are detected in men with nonbacterial prostatitis, then the PSA “should be evaluated in accordance with standard diagnostic approaches,” Dr. Gershman said.

About the Author

C.W. Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

C.W. Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, he has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by C.W. Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD Share

Counting steps is good — is combining steps and heart rate better?

Have you met your step goals today? If so, well done! Monitoring your step count can inspire you to bump up activity over time.

But when it comes to assessing fitness or cardiovascular disease risk, counting steps might not be enough. Combining steps and average heart rate (as measured by a smart device) could be a better way for you to assess fitness and gain insights into your risk for major illnesses like heart attack or diabetes. Read on to learn how many steps you need for better health, and why tagging on heart rate matters.

Steps alone versus steps plus heart rate

First, how many steps should you aim for daily? There’s nothing special about the 10,000-steps number often touted: sure, it sounds impressive, and it’s a nice round number that has been linked to certain health benefits. But fewer daily steps — 4,000 to 7,000 — might be enough to help you become healthier. And taking more than 10,000 steps a day might be even better.

Second, people walking briskly up and down hills are getting a lot more exercise than those walking slowly on flat terrain, even if they take the same number of steps.

So, at a time when millions of people are carrying around smartphones or wearing watches that monitor physical activity and body functions, might there be a better way than just a step count to assess our fitness and risk of developing major disease?

According to a new study, the answer is yes.

Get out your calculator: A new measure of health risks and fitness

Researchers publishing in the Journal of the American Heart Association found that a simple ratio that includes both heart rate and step count is better than just counting steps. It’s called the DHRPS, which stands for daily heart rate per step. To calculate it, take your average daily heart rate and divide it by your average daily step count. Yes, to determine your DHRPS you’ll need a way to continuously monitor your heart rate, such as a smartwatch or Fitbit. And you’ll need to do some simple math to arrive at your DHRPS ratio, as explained below.

The study enrolled nearly 7,000 people (average age: 55). Each wore a Fitbit, a device that straps onto the wrist and is programmed to monitor steps taken and average heart rate each day. (Fitbits also have other features such as reminders to be active, a tracker of how far you’ve walked, and sleep quality, but these weren’t part of this study.)

Over the five years of the study, volunteers took more than 50 billion steps. When each individual’s DHRPS was calculated and compared with their other health information, researchers found that higher scores were linked to an increased risk of

- type 2 diabetes

- high blood pressure (hypertension)

- coronary atherosclerosis, heart attack, and heart failure

- stroke.

The DHRPS had stronger associations with these diseases than either heart rate or step count alone. In addition, people with higher DHRPS scores were less likely to report good health than those who had the lowest scores. And among the 21 study subjects who had exercise stress testing, those with the highest DHRPS scores had the lowest capacity for exercise.

What counts as a higher score in this study?

In this study, DHRPS scores were divided into three groups:

- Low: 0.0081 or lower

- Medium: higher than 0.0081 but lower than 0.0147

- High: 0.0147 or higher.

How to make daily heart rate per step calculations

Here's how it works. Let’s say that over a one-month period your average daily heart rate is 80 and your average step count is 4,000. That means your DHRPS equals 80/4,000, or 0.0200. If the next month your average heart rate is still 80 but you take about 6,000 steps a day, your DHRPS is 80/6,000, or 0.0133. Since lower scores are better, this is a positive trend.

Should you start calculating your DHRPS?

Do the results described in this study tempt you to begin monitoring your DHRPS? You may decide to hold off until further research confirms actual health benefits from knowing that ratio.

This study merely explored the relationship between DHRPS and risk of diabetes or cardiovascular disease like heart attack or stroke. This type of study can only establish a link between the DHRPS and disease. It can’t determine whether a higher score actually causes them.

Here are four other limitations of this research to keep in mind:

- Participants in this study were likely more willing to monitor their activity and health than the average person. And more than 70% of the study subjects were female and more than 80% were white. The results could have been quite different outside of a research setting and if a more diverse group had been included.

- The findings were not compared to standard risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as having a strong family history of cardiovascular disease or smoking cigarettes. Nor were DHRPS scores compared with standard risk calculators for cardiovascular disease. So the value of DHRPS compared with other readily available (and free) risk assessments isn’t clear.

- The exercise stress testing findings were based on only 21 people. That’s far too few to make definitive conclusions.

- The cost of a device to continuously monitor heart rate and steps can run in the hundreds of dollars; for many this may be prohibitive, especially since the benefits of calculating the DHRPS are unproven.

The bottom line

Tracking DHRPS or daily activity and other health measures might be a way to improve your health if the results prompt you to make positive changes in behavior, such as becoming more active. Or perhaps DHRPS could one day help your health care provider monitor your fitness, better assess your health risks, and recommend preventive approaches. But we don’t yet know if this new measure will actually lead to improved health because the study didn’t explore that.

If you already have a device that continuously monitors your daily heart rate and step count, feel free to do the math! Maybe knowing your DHRPS will motivate you to do more to lower your risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Or maybe it won’t. We need more research and experience with this measure to know whether it can deliver on its potential to improve health.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD Share

Healthier planet, healthier people

Everything is connected. You’ve probably heard that before, but it bears repeating. Below are five ways to boost both your individual health and the health of our planet — a combination that environmentalists call co-benefits.

How your health and planetary health intersect

Back in 1970, Earth Day was founded as a day of awareness about environmental issues. Never has awareness of our environment seemed more important than now. The impacts of climate change on Earth — fires, storms, floods, droughts, heat waves, rising sea levels, species extinction, and more — directly or indirectly threaten our well-being, especially for those most vulnerable. For example, air pollution from fossil fuels and wildfires contributes to lung problems and hospitalizations. Geographic and seasonal boundaries for ticks and mosquitoes, which are carriers of infectious diseases, expand as regions warm.

The concept of planetary health acknowledges that the ecosystem and our health are inextricably intertwined. Actions and events have complex downstream effects: some are expected, others are surprising, and many are likely unrecognized. While individual efforts may seem small, collectively they can move the needle — even ever so slightly — in the right direction.

Five ways to improve personal and planetary health

Adopt plant-forward eating.

This means increasing plant-based foods in your diet while minimizing meat. Making these types of choices lowers the risks of heart disease, stroke, obesity, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and many cancers. Compared to meat-based meals, plant-based meals also have many beneficial effects for the planet. For example, for the same amount of protein, plant-based meals have a lower carbon footprint and use fewer natural resources like land and water.

Remember, not all plants are equal.

Plant foods also vary greatly, both in terms of their nutritional content and in their environmental impact. Learning to read labels can help you determine the nutritional value of foods. It’s a bit harder to learn about the environmental impact of specific foods, since there are regional factors. But to get a general sense, Our World in Data has a collection of eye-opening interactive graphs about various environmental impacts of different foods.

Favor active transportation.

Choose an alternative to driving such as walking, biking, or using public transportation when possible. Current health recommendations encourage adults to get 150 minutes each week of moderate-intensity physical activity, and two sessions of muscle strengthening activity. Regular physical activity improves mental health, bone health, and weight management. It also reduces risks of heart disease, some cancers, and falls in older adults. Fewer miles driven in gas-powered vehicles means cleaner air, decreased carbon emissions contributing to climate change, and less air pollution (known to cause asthma exacerbations and many other diseases).

Start where you are and work up to your level of discomfort.

Changes that work for one person may not work for another. Maybe you will pledge to eat one vegan meal each week, or maybe you will pledge to limit beef to once a week. Maybe you will try out taking the bus to work, or maybe you will bike to work when it’s not winter. Set goals for yourself that are achievable but are also a challenge.

Talk about it.

It might feel as though these actions are small, and it might feel daunting for any one individual trying to make a difference. Sharing your thoughts about what matters to you and about what you are doing might make you feel less isolated and help build community. Building community contributes to well-being and resilience.

Plus, if you share your pledges and aims with one person, and that person does the same, then your actions are amplified. Who knows, maybe one of those folks along the way might be the employee who decides what our children eat from school menus, or a city planner for pedestrian walkways and bike lanes!

About the Author

Wynne Armand, MD, Contributor

Dr. Wynne Armand is a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), where she provides primary care; an assistant professor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; and associate director of the MGH Center for the Environment and … See Full Bio View all posts by Wynne Armand, MD Share